The Journal Project

How do you get the most out of a journal? The key is simple: write stuff down.

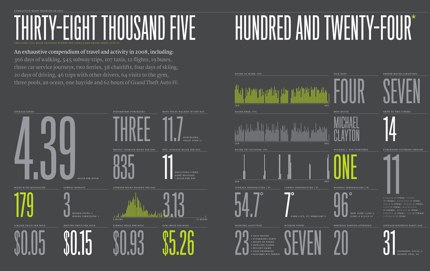

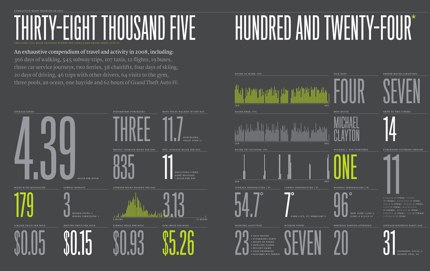

Christopher Felton’s annual report consolidates a host of mundane journal records into fascinating summaries and visualizations.

You can’t know in advance just what you’ll want to know later. You can’t do this the right way, you can’t do it optimally. As your needs and insights change, you’re bound to wish you’d recorded things you didn’t, and you’re likely to find many of the things you did record to be obvious, banal, and dull. (Don’t worry about that: you, or your biographer, might find those very things precious someday)

Some things are unpredictable: you’ll describe those in text. There’s no alternative. Nobody could have expected that to happen, and so you’ll have to start from the beginning.

But other things are more predictable, and you might want to have a regular slot in which to file the information you’ll record in every update. These slots offer you several advantages:

- You have a specific place to put a specific bit of information, making it easier to find later.

- The presence of the slot reminds you to record the information

- The type of the slot can remind you what sort of information you intend to record. Do you want a single name, or a list? Do you to record how far you jogged, or just whether or not you had your workout?

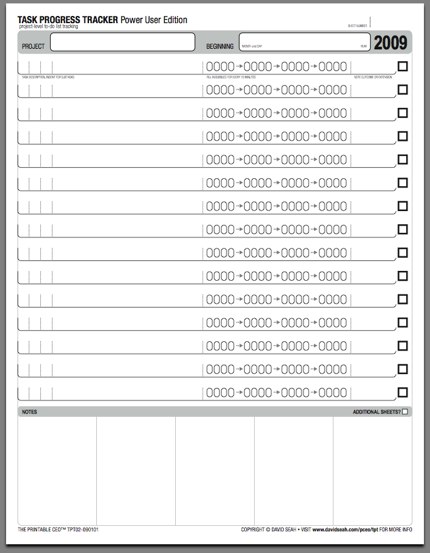

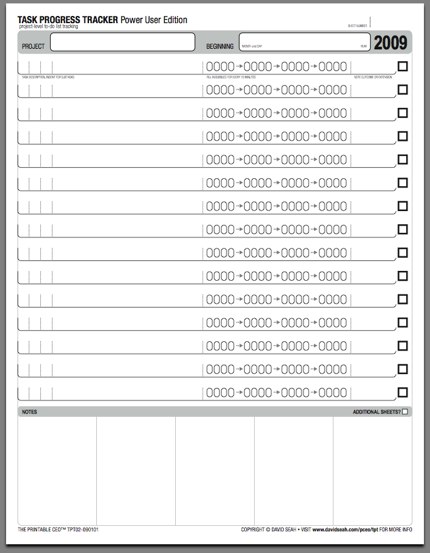

David Seah’s Printable CEO provides a variety of elegantly-designed paper forms for project planning.

The disadvantage of a long list of slots is tedium: confronted with a long and complicated form, you may find yourself too busy to fill out anything. This is especially onerous if some of the things you once thought might be useful you now know to be worthless. And, once you find yourself questioning whether or not parts of the form are worth filling out, the entire project can seem tarnished and tedious.

Still, without consistent records, Christopher Felton’s wonderful annual reports would never be possible. And, while you might overzealously set out to record everything you can imagine, there are bound to be some core elements you really want to track.

Kevin Kelly’s intriguing site on The Quantified Self gives a number of interesting examples. There’s also a Quantified Self Wiki.

This tension gives rise to a host of systems, templates, and forms that you can find in stationers and on the Web.

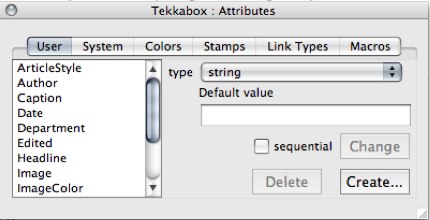

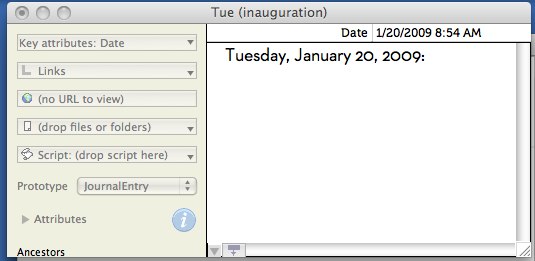

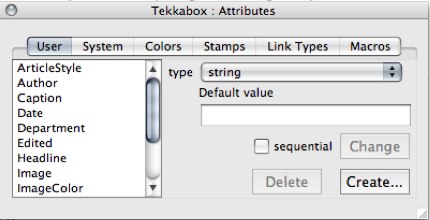

In Tinderbox , you can add metadata slot — Tinderbox calls this a Key Attribute, at the top of any text window by selecting any attribute from the key attributes menu or dragging it from the Attributes palette. You can make new attributes as well in the User tab of the Attributes palette. Most often, you’ll set the key attributes of a Prototype note, and let individual notes inherit those attributes.

Hint: you might have special key attributes for special days. You might, for example, want to record some information once a week, not every day; an easy way to do this is to arrange for every Saturday’s note to inherit from a special SaturdayPrototype.

Create new User Attributes by pressing Create… the attribute palette.

Some user attributes might best be numbers:

- blood sugar

- miles run

- weight

- words written in your next novel

Others might better be simple checkboxes, or dates. Sometimes, you'll want sets — lists of items, separated by semicolons.

- tags

- categories

- friends seen

- customers contacted

In planning a fresh Tinderbox , consider which kinds of metadata you are certain to need for each entry. Avoid the temptation to overload your system with dozens of slots, keeping in mind that, if you can always put information in the text of the journal entry and, later, formalize that information as a key attribute if it does prove useful to ensure its regular collection.

What do you track in your Tinderbox journal?

blog comments powered by

blog comments powered by

One reason people purchase ready-made journals instead of using a general-purpose notebook is that journals can come pre-printed with dates, page numbers, and other convenient boilerplate. These save some time, because otherwise you’d need to write the dates yourself.

Pre-printed forms can also remind you to record details that you might omit — especially details that now seem obvious. That’s why journals used to include the phase of the moon so prominently. Before streetlights and headlights, moonlight mattered; it was easier and more pleasant to go out in the evening when there was a moon. Everyone knew the current phase of the moon, everyone had a pretty good idea of when moonrise and moonset would be; it was simply part of the pattern of the day. But looking back, months or years later, you wouldn’t know — you’d have to look it up.

An easy way to pre-print information in Tinderbox is simply to use |= , the shorthand for conditional assignment. If the left-hand side of the assignment is empty, we proceed with the assignment, but otherwise Tinderbox ignores it. For example,

Text |= format($Date,"L")+": ";

means

If there’s no text yet, start out with the date. But if I’ve already put something in the text, leave the text unchanged.

This exemplifies a typical Tinderbox trade-off: we’ve had to so some work to set things up the way we want, but we gain lots of flexibility. We can preprint more information. We can format the date however we like. Yes, we could do this with some sort of Preferences dialog, but then we’d have another kind of complexity.

Note, too, that we don’t need to plan on doing this before we start keeping a journal. We could do without the date: it's nice to have, but we probably could manage without it. We could just write it out by hand: Pepys did! It doesn't take long, and some people fine this sort of work — numbering pages, writing in headings and indexes — a pleasant break. Emerson spent months preparing and then annotating and indexing his notebooks.

But, if you'd like the convenience of delegating the work to Tinderbox, is only takes a couple of minutes to add the action.

blog comments powered by

We can also add Rules to a prototype to enforce constraints. Where OnAdd actions are suggestions which you can overrule, rules are requirements: Tinderbox's rule manager runs constantly to enforce them.

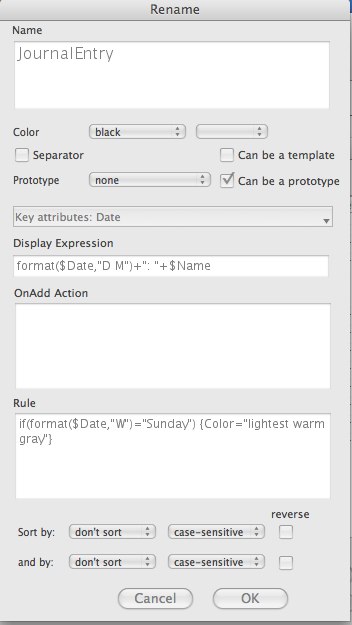

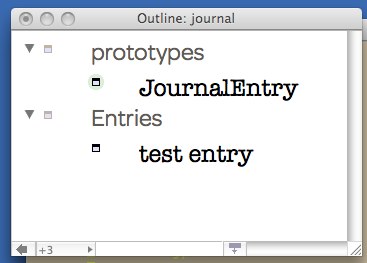

For example, let's add a rule to our prototypical JournalEntry:

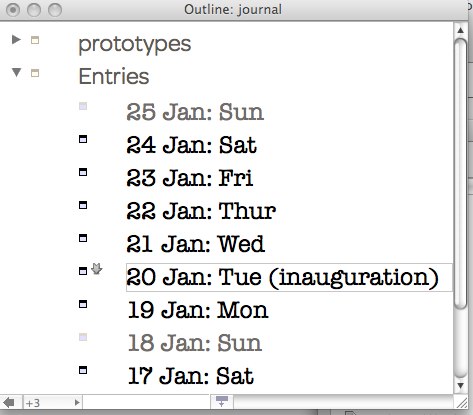

Entries on Sundays are light gray; all the rest are black.

This sort of zebra-striping helps the pattern of weeks stand out, and makes long lists easier to read. But it might not be right for you. Maybe you write a column that’s due on Tuesday and Friday. Maybe you want highlight alternate days. Lots of choices; that’s why we have flexible rules and not simply a menu of styles.

Think twice if you find yourself wanting Tinderbox to replace your calendar. Calendars are great, and repeating events are one of the things they do well. You could write a calendar in Tinderbox, but you're probably better served by letting the calendar do its thing and using Tinderbox to do stuff that nothing else can do.

The rule for our light gray Sundays is, simply:

if(format($Date,"W")="Sunday") {Color="lightest warm gray"} else {Color="black"}

And here's what it looks like in Outline view:

Perhaps we don’t want to use color to distinguish Sunday. We’ve got lots of other options. For example, we might choose a special font for Sunday:

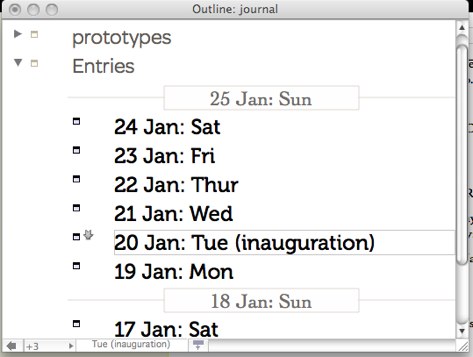

or we might let Sundays serve as separators:

if(format($Date,"W")="Sunday") {Separator="true"} else {Separator="false"}

blog comments powered by

Printed journals, planners, and diaries sometimes come with elaborate pre-printed forms. Indeed, sites like DIYPlanner and David Seah’s Printable CEO give you customizable templates for printing your own elaborate forms. These serve two purposes:

- They remind you of things you want to record

- They save time by pre-printing information, such as dates, that can be printed in advance

We can get some of these advantages in Tinderbox, too. For example, we can add Key Attributes to remind us of things we want to record, and we can automatically set attributes (like the Prototype attribute discussed earlier this week) when we know what their likely values will be.

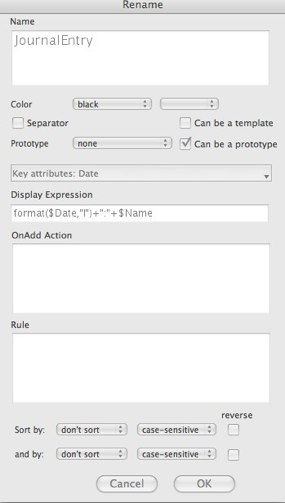

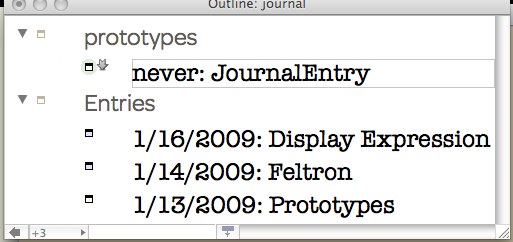

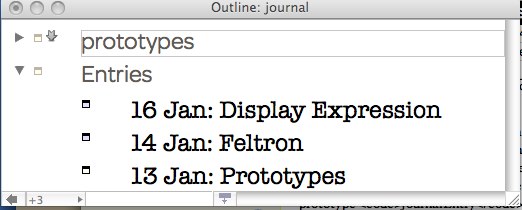

The attribute DisplayExpression is the Tinderbox equivalent of a running header; it lets us change the way Tinderbox displays the names of our notes. Normally, when Tinderbox draws a note, it simply takes the name from the attribute Name . But we can change this, and make it better. For example, let’s set the DisplayExpression of our prototype JournalEntry to:

format($Date,"l")+": "+$Name)

Now, every journal entry will inherit the display expression, and we'll see the timestamp before each title.

Perhaps we don't need to be reminded so often that it’s 2009; we can change the date format from "l" (local, short format) to "D M", giving us just the day and month

blog comments powered by

Nicholas Felton is 1 31-year-old New York designer. Each year, he compiles a gorgeous poster-size Annual Report that breaks down the things he’s done. THREE: pedometers purchases, TWELVE: most miles walked in one day, 38500 miles travelled (545 subway trips, 107 taxis, 38 chairlifts…)

Could we do this with Tinderbox ? Perhaps we won’t be able to automate away the lively tweaking of font sizes, or the clever and subtle choices of color highlights. But this kind of personal dashboard is well within our capabilities; we’ll be looking at some techniques later in the project.

Also of interest: Kevin Kelley’s Quantified Self Wiki.

blog comments powered by

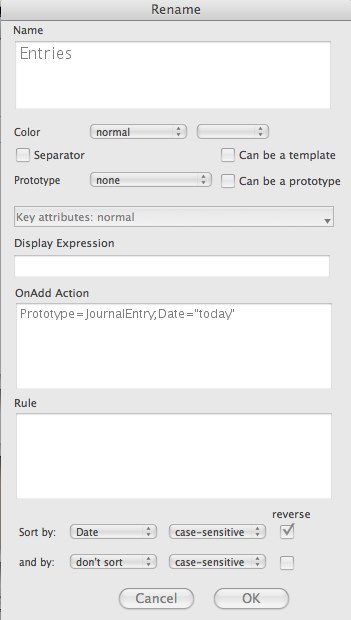

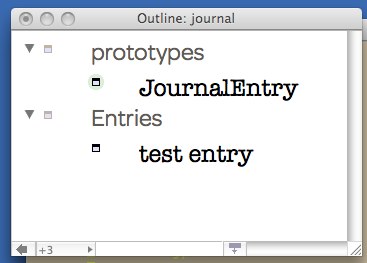

The entries in a journal will all likely share some things in common, whether we’re keeping a record of our blood sugar, tracking the freelance stories we’ve submitted to various editors, our simply recording the events of our schoolday.

Tinderbox lets you save time by associating notes with a prototype. When you assign a prototype to a note, you’re saying, “this note is just like it’s prototype, except for the differences I tell you about.” So, if we make a prototypical JournalEntry, all our journal entries will inherit its properties. For example, we might

- Add some key attributes (like Date) at the top of the text window

- Choose convenient and distinctive colors, patterns, and text background colors

We can do lots more with prototypes, but let's keep it simple for now.

It might seem a bother to make a prototype, and to have to set it every time you make a new entry — especially when, thus far, the advantages are just cosmetic. But it’s not a bother, because we can let the journal itself set the prototype:

OnAdd:Prototype="JournalEntry"

Note that this doesn't mean everything in our journal is a JournalEntry — just that things moved into our journal are assumed to be journal entries until we tell Tinderbox they're not.

While we're at it, we can also set the Date of the entry to “today”. That means that anything we drag into our journal from other containers, or that we create inside our journal, gets timestamped and is assigned a prototype. We can thus add a journal to another project: our research notes for our next screenplay, for example, could contain a separate journal for reflections on the creative process.

In just a few seconds, we’ve set up a journal with timestamps, automatic prototyping, entries sorted by date, and distinctive fonts and colors to distinguish journal entries from containers, metadata, and other stuff.

Time stamps are a great example of metadata: information that helps describe or situate your notes.

It’s nice to collect metadata automatically, because:

- most metadata is obvious now — and you may not foresee that it won‘t be obvious later

- most metadata is never useful

These days, digital cameras automatically capture lots of information about each picture: the date, the exposure time, the aperture, maybe the latitude and longitude. Using a film camera, you could write all this down (8x10 color glossies with a paragraph on the back of each one). But you probably didn’t. And so, maybe sixty years later, we’re looking at some pictures of our grandparents and “who are those other people?” and we really have no idea what we’re seeing. Where, if we had the idiotic camera taking notes, we’d at least know that this was photographed on March 27, 1964 in Riverside, Illinois, and so this must be Passover and that must be Aunt Jodi and Uncle Li and the little girl has to be Molly because Susan would already have been six or seven.

Tinderbox automatically records the time when you made a note, and the time when you last modified the note.

You can add the date to the text of the note (Edit:Insert Date or cmd-/), or the date and time (cmd-opt-/). If your computer is currently using (say) Norwegian, the date and time are formatted in Norwegian.

blog comments powered by

In the coming weeks, this column will explore a variety of ways to work with Tinderbox , Eastgate’s tool for making, analyzing, and sharing your notes. We’ll take a look at a series of projects, exploring a variety of rewarding tasks that show various aspects of Tinderbox in an interesting light.

This column builds on my book, The Tinderbox Way, emphasizing new Tinderbox features and a different mix of projects.

Specialized journals can be an invaluable business tool

To start the new column in the new year, we’ll look at journals and commonplace books — most generally, Tinderbox files that record things over a span of time. These range from personal diaries to research notebooks, from a naturalist’s field notes to a philosopher’s speculations. Specialized journals can be an invaluable business tool as well, and include not only the salesperson’s invaluable contact diary or the service organization’s complaint log, but also specific records of extraordinary events: project meeting diaries, say, or records of enterprise data outages or of emergency service issues with the company’s troublesome new filtration plant.

Knowing what you’ve done, and what you’re going to do, is a key. The first, necessary step, is to write it down: if you don’t record what happened, you won’t be able to analyze and learn from it later.

The second step, equally vital, is that you need to analyze and reflect. Simply making a record will help a little, because you’re bound to reflect on the experience as you record it. But you’ll also want to return and examine your record later. And that means you’ll want to explore, to select specifically interesting parts of the record and focus on especially significant facets.

You don’t know, as you start your journal, what sorts of analysis you’ll want to do in six weeks, or six years. You may suspect that some facets may be interesting, and so you’ll record those with care. You may speculate that some ways of organizing your journal will be productive and save you time later. Thinking ahead is always good.

don’t delay the real work

But it doesn’t matter if you get the initial organization wrong. This is the key to getting started with Tinderbox. Try something: you can always come back later and reorganize. Anticipate as well as you can what you’ll need, but don’t delay the real work by building complex systems. Don’t require yourself to fill out dozens of attributes you may not need; keep it simple (and pleasant), and add complexity as you discover that you need it.

blog comments powered by

© Copyright 2009 by Eastgate Systems, Inc. All Rights Reserved